The Blessing

蒙 福

Peter N. N. Wong

2001

It is understandable for someone to search for his or her roots, especially people living in a young country with many immigrants like Australia. As soon as I completed my first book “A Step Forward (勇往直前)”, my daughters encouraged me again to write something about my early life in Hong Kong and China. They are very interested in the family history and the things I had done in my early childhood.

The following account records my experiences during and after World War II. Most of the ancient family history was written on the basis of some old records, such as a family tree and notes kept by my brothers, Nai-King and Dennis. However, a limited verbal family history (during World War II) obtained from my relatives has been used in this document.

I would like to dedicate this writing to my late parents and my brothers and sister who have settled in different places in the world. I also hope that this document will be some help for our children and their children in finding their roots.

黃乃能

Peter N. N. Wong

Croydon, Victoria

Christmas 2001

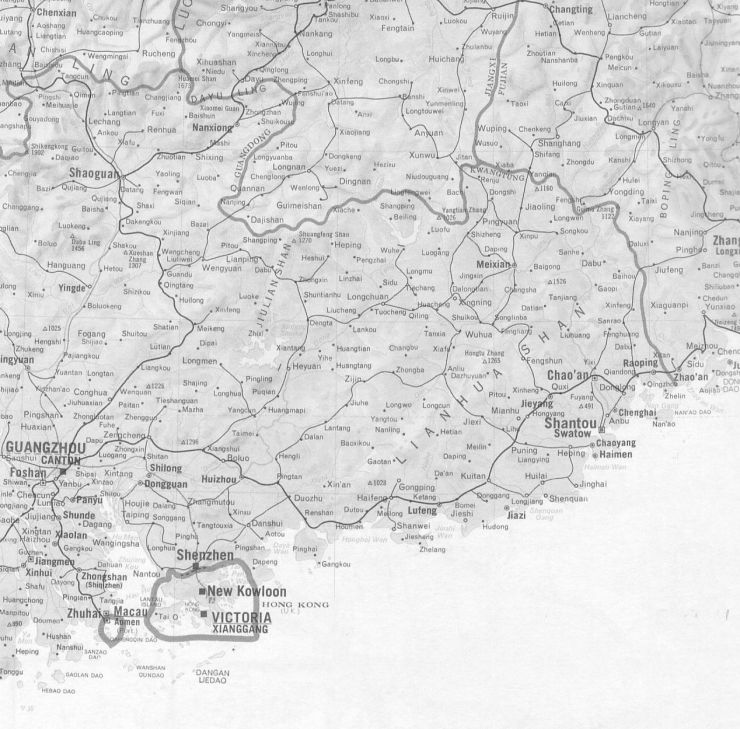

Front cover: The village of the Wongs (涌口村), Southern China, c.1950.

CONTENTS

PREFACE THE BLESSING 1 I. ONCE UPON A TIME 1 Origin of the Wong (Huang) Family 1 The New Life and New Home 1 II. THE CONCUBINE’S SON 3 Village of the Wongs 3 The Concubine’s Son 3 His Struggle and Success 4 III. BA AND MA 5 The Second Son 5 The Only Daughter 5 The Marriage 6 IV. DURING WORLD WAR II 9 Hong Kong – Pearl of the Orient 9 Japanese Occupation of Hong Kong 9 Escape to Foshan 10 Life in the Village 11 A Surprise Visit 15 V. RETURN TO HONG KONG 16 End of World War II 16 Return to Hong Kong 16 The Birth of Dennis 17 More War and Refugees 18 The Shop 19 Typhoon 19 A Big Family 20 VI. THE CHANGING POINT OF MY LIFE 21 A New School 21 My Sickness 21 The Turning Point 22 VII. THE HIGH SCHOOL YEARS 23 A Significant Step 23 All Saints High School 23 Clementi Middle School 24 Kowloon Riots 25 Chinese New Year 26 Cantonese Opera 26 Mahjong 27 Hiking and Camping 28 The Funeral 29 VIII. LONGING FOR BETTER 31 Leaving Certificate Examination 31 Preparation for Tertiary Study 31 A Dream Come True 32 EPILOGUE 33 ATTACHMENTS 34 Attachment 1: Huang’s Origin 34 Map 1 –Migration of the Wongs to Guangdong 37 Map 2 –Migration of the Wongs to Pearl River Delta 38 Attachment 2: The Wong (Huang) Family Tree 41 - Before migration to the Pearl River Delta 41 - After settling in Yongkou Village in Nanhai County 42 Attachment 3: My Father’s House 43 Attachment 4: Photographs 44

蒙福

“We are hard pressed on every side, but not crushed; perplexed, but not in despair; persecuted, but not abandoned; struck down, but not destroyed.” (2 Corinthians 4:8-9)

“I will bless them and the places surrounding my hill. I will send down showers in season; there will be showers of blessing.” (Ezekiel 34:26)

Origin of The Wong (Huang) Family

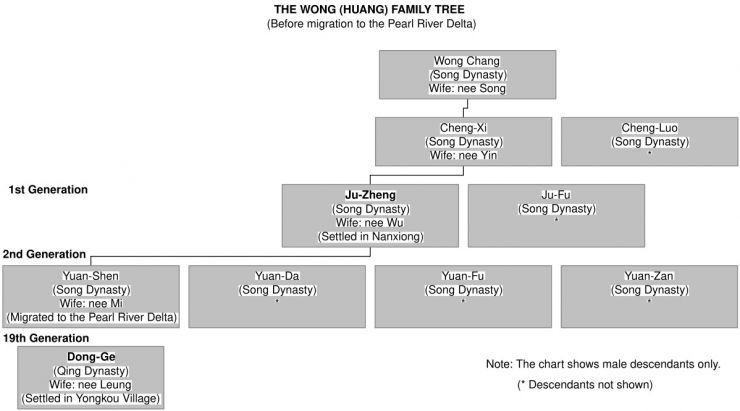

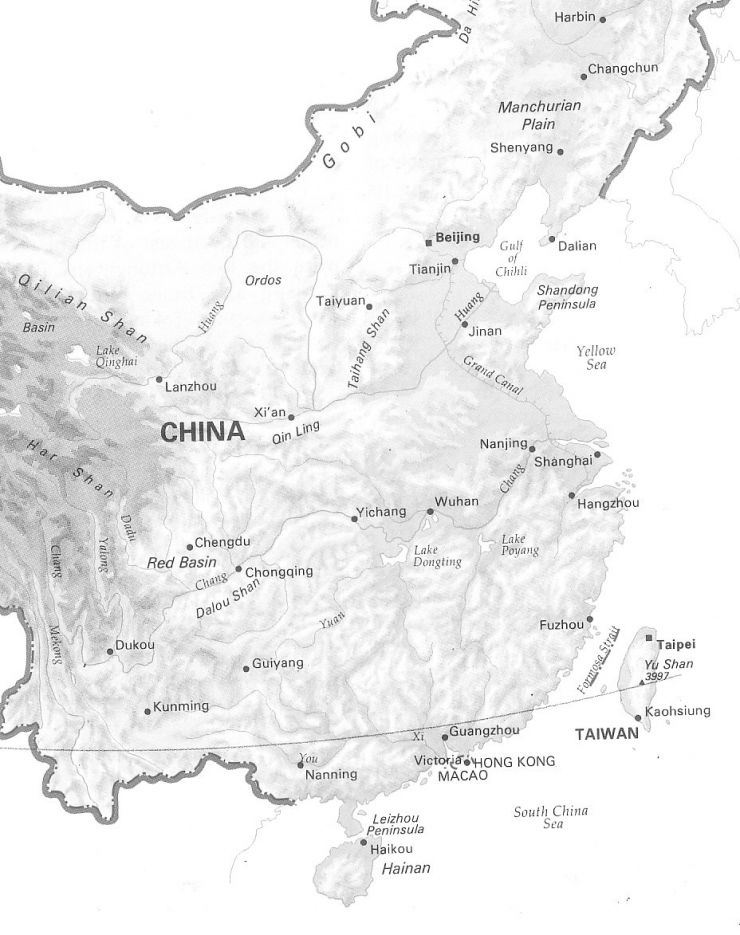

I don’t know exactly when and how the forefathers of the Wongs (黃, WONG for Cantonese and HUANG for Standard Chinese) migrated from north of Guangdong province (廣東 or Kwantung) to the south and settled in our village on the Pearl River Delta (珠江三角洲). Refer to Attachment 1 – Maps 1 & 2. I haven’t seen any written records detailing their lives and experiences other than a few brief notes obtained from other sources. All I have is a limited verbal history from my relatives, which has yet to be confirmed. Following is a brief account of our ancestors before migrating to the south of Guangdong.

During the Song Dynasty (宋, 960-1279), our forefather Wong Ju-Zheng (黃居正) returned from Fujian (福建) to Guangdong (c.1175) and settled in a place called Zhu Ji Xiang (珠璣巷) in Nanxiong (南雄), a town close to the borders of Guangdong and Jiangxi (江西) provinces. He was the first generation of the Wong (Huang) Family to settle to the south of Guangdong. (Refer to Attachment 1 – Origin of the Wong Family.)

Wong Ju-Zheng married Wu (巫氏) and had four sons - Yuan-Shen (源深), Yuan-Da (源大), Yuan-Fu (源輔) and Yuan-Zan (源贊). Wong Yuan-Shen married Mi (米氏) and was a Royal Officer (漕運使), responsible for delivering grains and supplies as tax to the Emperor (c.1181). The Wongs in our village are possibly the descendants of Yuan-Shen. (Attachment 2 – Family Tree)

As I mentioned earlier, I don’t know when, why and how our forefathers migrated from Nanxiong to the south of Guangdong. There are many versions of the migration story (Refer to Attachment 1). It is very hard to prove which one is for our ancestor who settled in a village in Nanhai County (南海縣). (Somebody suggested that the migration was to escape from prosecution caused by an event related to the Emperor’s Concubine Wu (胡妃之禍). But it is only a verbal tale and has yet to be confirmed.)

The exact route of our forefathers travelling from Nanxiong in the mountainous Dayu Ling (大嶼嶺) region to Foshan (佛山) on the beautiful and fertile Pearl River Delta is not clear. I can only guess that they would travel along the Zhen River (湞水) then North River (北江 or Bei Jiang) and eventually arrived in Nanhai County, which situated between the North River and Pearl River (珠江 or Zhu Jiang) near Guangzhou (廣州 or Canton). It is possible that they travelled part of their journey by foot and part by boat. I also don’t know how long they did take to settle in our village near Foshan. Other descendants of Wong Ju-Zheng settled in many places, mainly on the Pearl River Delta. (Refer to Attachment 1).

During the Qing Dynasty (清朝, 1644-1912), the first forefather to settle in our village in Nanhai County was Wong Dong-Ge (黃東閣), the 19th generation of the Wong Family. (Refer to Attachment 2.)

The Pearl River Delta situated in a subtropical zone, enjoys a warm climate and abundant rainfall. The main produce of our County is rice, vegetables, fish and poultry. The weather and the soil are so good that we can harvest the rice twice per year. Our village is near the City of Foshan (two hours journey by foot) and the provincial capital city Guangzhou (half day journey by boat). Therefore, the villagers are also actively involved in trading and village industry. It is a blessing that we were never short of food, even in the difficult time during World War II.

I haven’t been back to my village since I was a small boy. (My family moved to Hong Kong and eventually settled there after World War II.) Our village has changed so much in the past twenty years that I may have difficulty in recognising it now! The recent main additions to the village are a multi-storey community building (Joss house) near the village pier, a new highway on the other side of the river and a road bridge connecting the highway to the village. However, I still keep a fond memory of the “old” village, where I had spent a few happy years in my early childhood. (Photo 1)

Our village (Yongkou Village 涌口村) is nicknamed the “Village of the Wongs”, because most of the villagers are our relatives and have the same surname, Wong. In front of the village, there was a 20 metre wide river, one of the North River tributaries. In the wet season, the water in the river was deep enough for barges travelling from Guangzhou up to the village pier. We used the water drawn from the wells in the village for cooking, but used the water of the river or creeks for farming.

During World War II, the population of the village was over 200 people. We lived close together in the narrow lanes. The houses of the village were built on the flat ground of the riverbank; in fact we hardly saw any hills from the village. Our village was surrounded with rice fields and vegetable gardens, together with a few small creeks flowing in between. A large pond with water lily was located near the river pier. It was also used as a fish farm. Different kinds of nice trees lined both side of the road leading into the village. And many fruit trees were planted along the small creeks adjacent to the village.

The large buildings in the village were the joss houses and temples. One of the joss houses was used as a primary school. It was one of the best-run schools in the County. A high school was built near this primary school a few years later, after I had left the village. Our village was beautiful and a peaceful place to live in.

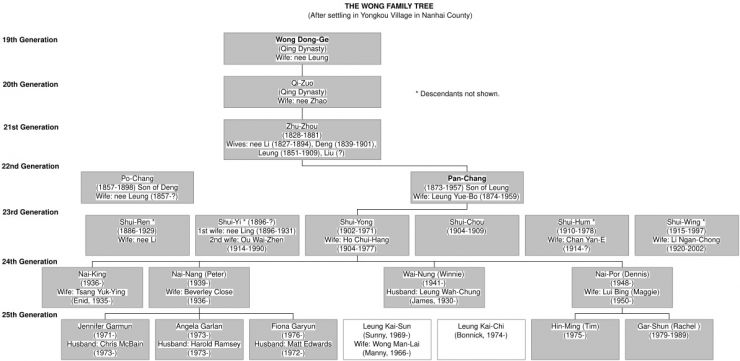

Our great grandfather Wong Zhu-Zhou (黃著洲, 1828-1881) was the 21st generation descendant of the Wong Family. (Refer to Attachment 2) He was rich (compared with other villagers) and had one wife and four concubines. Zhu-Zhou had two sons but no daughter. His first concubine, Deng (鄧氏, 1839-1901), presented him with the elder son Po-Chang (普祥, 1857-1898). And his second concubine, Leung (梁氏, 1851-1909), presented him with another son who was our grandfather Wong Pan-Chang (黃攀祥, 1873-1957). Leung was 23 years younger than her husband. The fourth concubine ran away from Zhu-Zhou, therefore, we have no name or record of her.

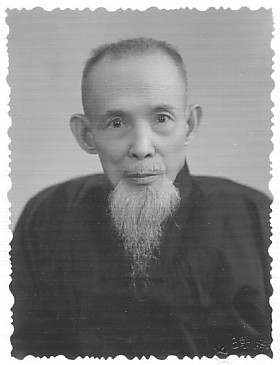

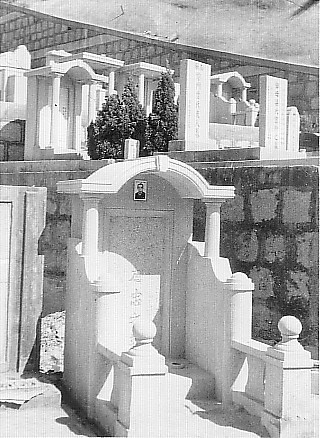

Grandfather Pan-Chang (Photo 2) was born prematurely, but lived for 84 years. His mother was pretty, uneducated but a kind-hearted woman. She was born to a poor family not far from our village in the same county. Grandfather’s brother Po-Chang was many years older than him and did not have a close brotherly relationship because of the large age gap between them. Grandpa had only a minimal education and was sent to work in Hong Kong at a young age.

Our grandfather left his beloved mother in the village, all by herself. Her husband had died a few years before and nobody could care for her adequately in the family. Pan-Chang promised his mother, “I will work hard, learn as much of the trade as I can and look after myself in Hong Kong.” He prayed that he would be successful and rich one day and could give his mother a comfortable home for her remaining years. Due to his painful family experience, our grandfather had one wife only in his whole life and instructed his descendants that no one would have any concubines in his family.

Grandfather Pan-Chang travelled to Hong Kong alone and started working as an office boy in a small bank (錢莊) of his father’s friend. He worked very hard and long hours in the bank, and picked up the trade skill and business knowledge as quickly as he could. Pan-Chang was polite to everybody, good in figures and trustworthy. No wonder that he was promoted to a higher position in the bank within a short time.

He sent part of his salary to his mother every month and saved most of the remaining money in his bank account. He didn’t waste any of his hard earned money in drinking or gambling, like other staff did. After a few years, he had saved a small sum of money for investment.

In the beginning, he invested his savings in shares and money lending, but the investments did not give him profitable and reliable returns. He had thought about doing other business, however, he didn’t have enough capital for the proposed investment. He waited for a few more years until an opportunity came up for him to invest in property with his friend. They pooled all their money together and built a house, then sold it for a good price. The profits of the first house gave him enough money to invest in the second house by himself alone. After a few times of building and selling houses, our grandfather had saved enough money to try on bigger ventures.

Pan-Chang used his business knowledge and trading skill obtained from the bank, in his new business ventures. He invested in various businesses, including insurance, Chinese wine, textiles, property and rice farming. Most of his investments were very successful except the textile factory. Due to ill health our grandfather retired from business around 35 years of age.

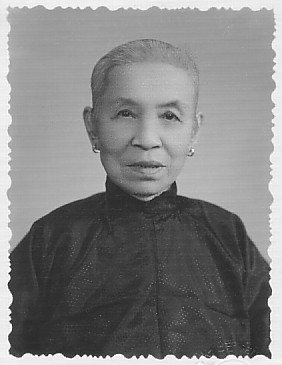

He married our grandmother Leung Yue-Bo (梁月寶, 1874-1959) a few years after he went to Hong Kong (Photo 3). She was born to a middle class family not far from our village in the same county. Grandmother was strong and active, even with her bound feet. She gave him five sons, but one died at an early age. The remaining four sons were Shui-Yi (兆義, 1896-?), Shui-Yong (兆勇, 1902-1971), Shui-Hum (兆堪, 1910-1978) and Shui-Wing (兆永, 1915-1997). They are the 23rd generation of the Wong family. (Refer to Attachment 2)

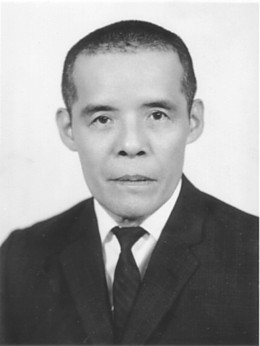

Our father Shui-Yong was the second son of the family. (Photo 4) He didn’t have a high education but was strong as a horse. Shui-Yong was of medium height with wide shoulders and a muscular body. He always kept his hair short for easy looking after. Ba (Chinese for father) had a nice character like his father - gentle, reliable and hardworking. Our grandfather always wanted his second son to accompany him on all his business trips.

The other three sons of grandfather received a higher education. The first son, Shui-Yi, studied accountancy/customs in the Peking University and could speak English fluently. The fourth and fifth sons, Shui-Hum and Shui-Wing, both had a high school education and once taught in the primary schools. Both our father and mother received an education equivalent to a primary school or the first year of high school level. For this reason, they always longed for their children to have a higher education.

Shui-Yong started working for his father in his late teens. It was partly because he was not a promising student and partly because he was wanted to assist his father in the family business. Ba learned all the skills of trading from his father and his father’s business partners, including Chinese wine making. He was a real gentleman, respectful son, faithful husband and a loving father. Our father was not the most favoured son of his mother, but he had the last and only blessing from his dying father.

Our mother Ho Chui-Hang (何翠杏 or何杏, 1904-1977) was born to a middle class family about half hour walking distance from our village. (Photo 5) Ma was a tiny woman and had an attractive face and a kind heart. She loved her family and would do anything for them, but she also believed in good training and discipline.

Ma’s forefathers migrated to the south for similar reasons as the Wong Family. My mother was told, without confirmation, that her surname was Han (韓) before the migration. But they changed it to Ho (何) due to a mistake or misunderstanding of the locals when they arrived on the Pearl River Delta.

“Her forefathers travelled to a place near a river in our region and asked for help from the locals. The villagers didn’t understand what they wanted because they spoke a different dialect. In order to make the locals understand their surname was Han, the same name as a river called Han in southern China, they communicated with the villagers in sign language and pointed to the river next to them. The locals mistakenly thought that their surname was Ho, which has a similar pronunciation as river (河) in Chinese. Therefore, they were sent to the nearby village of the Ho’s. From that time they settled happily in the Ho’s village and began to use the surname Ho.”

Ma’s father Ho Nai-Poon (何迺盤) was a trader travelling between Guangdong and Guangxi provinces many times per year. He bought and sold herbs or local produce for good profits, but with some degree of risks in his journey. When she was a little girl, Ma’s father fell sick in one of his trading trips and died very soon after he arrived home. Her mother Yip Po-Kam (葉寶淦) was a nice person whom, unfortunately, I never met. Ma had a younger brother but he died at an early age. Therefore, she grew up as an only child in her family.

Ma didn’t have a formal education like we did. She was taught to write and read by her own mother. She then attended a class in a private home in the next village, which had been specially arranged for a few lucky young girls. Ma could write and read reasonably well and even do some arithmetic! She was an excellent cook and dressmaker (making most of our clothes when we were young). Ma could also do very nice embroidery, which she had learned as a teenager from her mother.

When Ba was in his late teens and working in Hong Kong, his parents decided that it was time for them to find Ba a suitable wife. They engaged a matchmaker who then sent out enquiries to the villages with suitable young girls in our County.

The matchmaker took the birth time and date of Ba to match with the selected young girls. She checked the birth time and date of the girls to decide who would bring good luck to Ba. Then the matchmaker would recommend a most suitable girl (or girls) to our grandparents for consideration. Grandfather would investigate the family background of the girl, including her character, education, wealth and health. If everything went well, our grandparents would inform the matchmaker of their decision and request an interview of the girl.

The matchmaker went to see the particular girl’s family and arranged the interview. Usually, the first interview (if they didn’t know the girl’s family personally) would take place in a public place, such as a park, temple or marketplace. Ba and his parents would observe the selected girl, Ho Chui-Hang, this first time without the girl knowing about it. If he liked the girl, a second interview could be arranged in a restaurant or an outing to meet each other face to face. Obviously, our father liked Ho Chui-Hang very much and asked his parents to arrange their engagement.

The engagement was an important step before their wedding. The matchmaker found out what the girl’s family would accept as a gift for the engagement as well as the wedding, and suggested a date for the wedding. The time between the engagement and wedding could be one to three years. After the engagement, Ba and Ma could go out together by themselves, but not before.

When the time came close to the wedding, the matchmaker again went to see Ma’s family and negotiated an acceptable wedding arrangement with her mother (her father died many years before) on behalf of the Wong Family. After going backward and forward a few times, a final agreement was reached. And the preparations for the wedding would shift into top gear. A room in the Wong’s family house was prepared for the bride and groom, and the bride’s family would provide some of the furniture for their new home.

In the morning of their wedding day, Ba dressed in his new robe and put on his special hat, and walked to Ma’s village accompanied by his close friends. He asked her mother’s permission to take Chui-Hang home. She gave him permission but sent him ahead of Ma, because Ma would like to stay with her family a little longer as a sign of respect to her mother and relatives.

Ba went home and waited patiently for the arrival of the bride. Ma put on her red wedding dress and travelled to our father’s village on a four-bearers red sedan chair. The red sedan chair was made of wood and had a water-proof roof and beautifully decorated walls. The wedding procession included also the representatives of her family, matchmaker, servants, flag and lantern bearers, musicians and the gift carriers.

When the wedding procession arrived in the village, the villagers let off firecrackers to scare off the evil spirits and in the same time welcomed the bride. The bride was then ushered into the house and got ready for the marriage ceremony. After the groom and bride gave their vows of marriage, the bride would present a cup of tea to her father-in-law, then her mother-in-law. She would also give a cup of tea to each elder of the family. In return, she would receive gifts from her parents-in-law and the family elders.

Following the marriage ceremony, the guests were invited to a big wedding feast. A proper feast would have eight to ten courses and take three or more hours to have the meal. The first two courses were entrees; one cold and one hot. Plenty of rice wine or sorghum spirit would be served to the guests. The next course would be soup, then the main courses including various seafood, poultry, meats and vegetables. The last two courses would be noodles and fried rice, and fruits and dessert (cake, bun, etc.). The menu should include BBQ pork, chicken and fish for good luck. In order to thank the guests, the bride and groom would go to each table and drink (or pretend to drink wine) with them.

After the feast, it was the time for the groom’s young friends to play jokes on the new couple. One of the popular games they would play was making the newly wedded couple eat an apple together without using their hands; the apple was hung with a string from the ceiling. As you may know, kissing in public was not a done thing in China at that time! Sometimes, the groom’s friends might even make him drunk and tease the bride into the late evening.

The next morning, with the help of her maid, Ma got up early to prepare breakfast for the family. She presented the breakfast to her parents-in-law, as the duty of a new daughter-in-law. Some of the guests would stay and continue the celebration with the family until the second day after the wedding. In the third day of their marriage, Ba would go with Ma to visit her own family (回門) and present his new mother-in-law with a small BBQ pig in gratitude for bringing his new wife up as a nice and respectful lady.

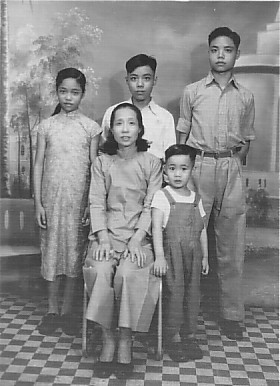

Ba and Ma married in 1923. Ba was 20 years of age and Ma was 19. Ma eventually presented him with four children, three sons (Nai-King 乃經, Peter 乃能, Dennis 乃波) and one daughter (Winnie慧儂). We are the 24th generation of the Wong family (Photo 6). (Attachment 2)

One month after their wedding, Ba went back to Hong Kong to work, and Ma stayed with her in-laws in the village in China. Ba came home to see Ma only during the main holidays of the year. The situation was not ideal for the new couple, but that was life in the olden days. Eventually, Ba took Ma to Hong Kong to live in our grandfather’s apartment at Sham Shui Po (深水涉), a suburb on the Kowloon Peninsula (九龍半島).

Hong Kong –Pearl of The Orient

Hong Kong was a British Crown Colony until it was returned to China on 1 July 1997. Before the Handover, some of the Hong Kong Chinese reckoned this Colony to be a “three-legged stool”, with one leg in Beijing (Peking), another in London and the third in Hong Kong. If one leg were chopped off just a wee bit, the stool would be askew. If the legs become even more unequal in length, the stool tilts crazily and doesn’t fulfil its original (and stabilizing) function. Hong Kong has become a Special Administrative Region (SAR, 特別行政區) of China from the day of Handover. The Sino-British agreement enshrined in a joint declaration allowed for Hong Kong to retain its unique social, economic and legal systems for at least 50 years after 1997. The Chinese catch phrase for this arrangement is “one country two systems (一國兩制)”, meaning Hong Kong is permitted to retain its capitalist system after 1997 while across the border the Chinese continue with a system which they label socialist.

Before colonisation, Hong Kong was a small fishing village and occasionally used as a hiding place by pirates. In 1842, the Treaty of Nanking (南京條約) gave the island of Hong Kong to the British. In 1860, the peninsula of Kowloon and Stonecutters Island (昂船洲) were added to the Colony. It was expanded in 1898 when England received a 99-year lease from China for the mainland and island regions called the New Territories (新界). The total area of Hong Kong is approximately 1060 square kilometres, with a population over 6 million before the Handover.

Despite a shaky start, during the latter half of the 19th century and the early 20th century Hong Kong flourished as a trading centre, an intermediary between China and the rest of the world. The colony had undergone industrial expansion since World War II. In addition to the old industry of shipbuilding and ship repairing, a number of new industries had sprung up, such as textiles, footwear, enamelware, aluminium ware, plastics and rattan ware. Hong Kong is a free deepwater port. Goods from all parts of the world come to Hong Kong to be stored, sold, and reloaded. The high-tech industrials developed recently in Hong Kong are electronics and computer. In the 1990s, Hong Kong has become one of the most important financial centres in the world.

Japanese Occupation of Hong Kong

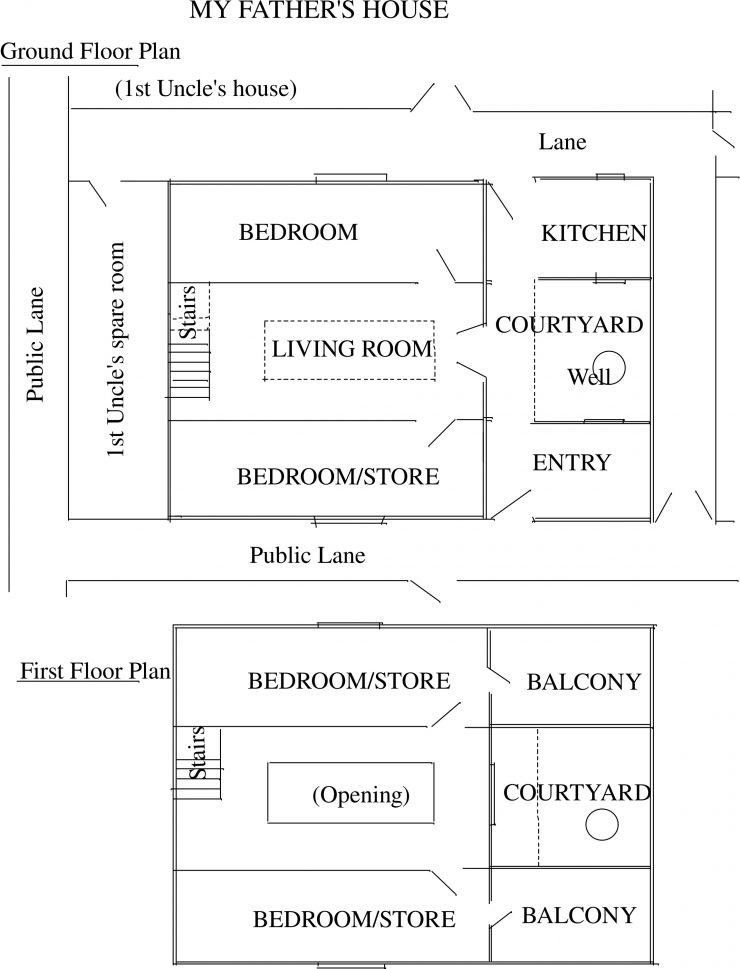

By the time of his retirement, grandfather Pan-Chang had invested most of his money on properties in Hong Kong, and rice fields in China. He owned five houses in the village –grandpa and grandma lived in one house, and his sons lived in the other four. Our father’s house was a new two-storey house (Attachment 3). Grandfather bought a large house in Guangzhou for the second marriage of his first son Shui-Yi (his first wife, Ling, died without children many years before). Unfortunately, this beautiful house was bombed and destroyed completely during the Sino-Japanese War. Grandfather also owned six three-storey buildings at Sham Shui Po, Hong Kong. The fourth uncle’s (Shui-Hum) family and our parents lived together in one of grandfather’s apartments (one floor of his buildings) in Hong Kong, before the Japanese occupation.

Ba and Ma spent the major part of the year in Hong Kong, but they had a few short stopovers in Guangzhou en route to our village. They visited the village in China a few times each year, usually during the main Chinese festivals. Grandparents and other uncles and aunts would visit them in Hong Kong from time to time throughout the year.

My elder brother Nai-King was born in Guangzhou 1936 (the year of the Rat). He was the second grandson of the Wong family but the first grandchild of the Ho family. You may imagine what joy it brought to the baby’s parents and his grandparents.

In 1937, the Sino-Japanese War erupted. Guangzhou fell to the Japanese a year later. The population of Hong Kong increased suddenly, from less than 1 million people before 1937 to approximately 1.7 million after the fall of Guangzhou, due to many people fleeing from war-torn China to the more secure Colony of Hong Kong. Our grandparents and the families of the other two uncles also moved to Hong Kong for stability and safety.

I, Peter Nai-Nang, was born in a birth clinic in Hong Kong 1939 (the year of the Rabbit). Two years later, a baby girl, Winnie (Wai-Nung), was added to our family. She was born in the same birth clinic in 1941 (the year of the Snake), just a few months before the Japanese army invaded the Colony.

Following the attack of Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941, the Japanese invaded and eventually occupied Hong Kong on Christmas Day the same year. However, Japan recognized Portugal’s neutrality and tiny Macau, about 65 kilometres west of Hong Kong, became a refuge for escapees who successfully ran through Japan’s military gauntlet.

In the years of the Japanese occupation, a shortage of food led many people to return to China. By the end of World War II the population of Hong Kong was reduced to approximately 600,000.

I was too young to remember the details of our escape from Hong Kong to Foshan. The following is a brief account of the event obtained from my mother.

A few days before the Japanese attacking the Colony, our family had to leave our secure and comfortable home in Hong Kong and return to China. In a late afternoon, our grandparents, the families of uncles and our own family boarded a boat in Hong Kong and sailed to the Pearl River Estuary. We travelled from Hong Kong to Guangzhou all night, with strong winds and rough seas. Conditions improved significantly when the boat sailed into the Pearl River near Canton, but we had to take a dangerous manoeuvre of crossing the Japanese blockade into the occupied region under the cover of darkness, just before dawn. We travelled the remaining journey from Guangzhou to Foshan either by bus or train (I am not sure!). It was not an easy journey for any of us, especially travelling with a few-months-old baby.

We lived in a big rented house in Foshan, not far from the ancient Taoist temple Zumiao (祖廟). Grandfather thought it would be safer for all of us staying in Foshan than in our village. Ba didn’t stay with us in Foshan, but lived alone in Hong Kong in order to look after the family properties during the Japanese occupation.

Foshan is located in the northern part of the Pearl River Delta, adjacent to Guangzhou. It is a medium-sized industrial city and has a history of over 1300 years. The city covers an area of 77 square kilometres with a population of more than 250,000 in the mid 1980s. Being one of the four famous ancient towns in China, its pottery-making, metal-casting and silk-weaving handicraft industries have been prosperous since the Song (宋) Dynasty. After World War II, its industries expanded rapidly, including machinery, textiles, light industry, chemicals, electronics, ceramics and other new developments.

During the Japanese occupation, Ba joined the local volunteer fire brigade in Hong Kong. Using his connections with this local group, he was able to keep the family properties from looting and damaging. Life was not easy for him in Hong Kong. The harassment of the Japanese soldiers, frequent bombings from the Allies and short of food, fuel and other essential things in Hong Kong made his life very hard, lonely and unbearable. He missed us very much. The only comfort for him was a photograph of our family, which he treasured dearly and always kept in his wallet.

Our life in Foshan was not too bad, compared with the life in occupied Hong Kong. We had plenty of nice food to eat and a comfortable house to live in. We even visited the mysterious ancient Taoist temple Zumiao and the beautiful Xiuli Lake (秀麗湖) many times during our short stay in this city. We lived in Foshan only for a few months, until it was safe enough for us to return to the village in Nanhai County.

I was too young to remember all the things that happened in Foshan. The only thing I can remember (it may also be the first thing which I can remember in my early life) was an event in the dining room of the rented house. I still have a hazy picture of my younger cousin Nai-Ping (乃平) who sat by the dining table and waited for his meal. He was hungry and cried for attention. I was surprised to see a big bubble suddenly come out from his mouth. My cousin was surprised too. He stopped crying immediately and even forgot his hungry feeling completely.

In mid 1942, we returned to and settled in our peaceful and beautiful village in Nanhai County. The war situation was still not very good, especially conditions in Hong Kong. Ma communicated with Ba by letters, but the mail service at that time was not reliable; it might take about two weeks to deliver a letter.

During the War, we were always aware of robbery and kidnapping in our County. A telephone line was set up especially in our area for emergency communication between the nearby villages. Our village had a self-defence agreement with the other six villages in the district. If one of the villages was attacked, the other six villages would come to its defence. For this reason, our district was reasonably safe from bad people, compared with other areas.

All of our grandfather’s rice fields were leased to the local farmers. We received a part of the grain and hay as rent when the rice had been harvested. The farmer usually delivered our share of grain to our house, but we had to collect our share of hay from the field. The dried hay was used as fuel for cooking and sometimes used to protect the young vegetables from frost in our garden during winter.

It was good fun for us kids to help the adults collect hay from the field. I was told to carry some of the hay bundles back to the storage shed in the village with one of my cousins (Tony, 乃敦). We set out happily to the rice field at the rear of the village. Between us, we carried two bundles of hay with a bamboo pole on our shoulders; my cousin carried one end of the pole at the front and I carried the other end at the back. We walked on a narrow path between two rice fields and joked to each other on our way home. Suddenly, my cousin stopped on the path and indicated that he saw a hole in the field, which could be a rabbit warren. He went hurriedly to investigate and accidentally fell head first into the hole with his legs kicking in the air. It was funny to see his struggles, but I couldn’t pull him out from the hole. I raced back to the field to get help. Eventually, his mother came and pulled him out from the hole. My cousin was frightened but not hurt.

Both Nai-King and myself attended the village school, Qing Xi Primary School (清溪小學), located near the river. My first uncle Shui-Yi was the principal of this school (he also taught English fulltime in a high school in Guangzhou). Our school was the best equipped primary school in the district. Each morning and late afternoon, we assembled and marched in front of the school, to raise or lower the flag. We had three teachers for a total of six classes in the school. Some of the small classes were combined in one classroom for easy handling. The school had a small brass band (for the older kids only), a small library and a large vegetable garden. We had plenty of space in the school for playing games or sport during recess. The school was funded from the estates of the Wongs, accepting both boy and girl students. The school fee was very low and even free to the kids from poor families.

In the afternoon after school, my elder brother Nai-King might have a ride on the back of his friend’s water buffalo. Sometimes, he might even have a water buffalo race in the field with his friends without our mother knowing. Other things Nai-king would like to do in the village were swimming in the river and climbing trees to fetch bird’s eggs.

After the farmers finished harvesting potato, sweet potato or carrot in the field in the autumn, we would love to fossick in their vegetable gardens and hunt for leftovers in the ground. We usually worked in a group and gathered all we could find for a roast potato or sweet potato feast around a campfire. However, I would like to keep a few of the small carrots in my pocket and eat them raw in the classroom during lesson. We did similar things in summer, but hunted in the ponds for water chestnuts or water lily roots.

During the Chinese New Year, we had two big feasts to celebrate the beginning of a new year. Unfortunately, the feasts were for the males only. The first feast, “Family Feast (家飲)”, was a vegetarian meal (but a small amount of meat was usually provided!) and would be held in one of our joss houses in the early morning of New Year’s Day. The second feast, “District Feast (鄉飲)”, would take place in turn in one of the seven villages, a few days after New Year’s Day. This feast was important to the villagers, because it helped to promote friendship, education and respect and reduce any misunderstanding among the people of the villages.

Any male of these seven villages would be invited to the feast, if they were an official representative of the village, an elder of the village, a scholar with an education above primary school, or currently a student. A sedan chair would be provided for the guests who were sixty-five years of age or over. A specially made ceremonial silver cup (jue or 爵) would be presented to the elders who had just turned seventy years of age. My grandfather longed to receive this cup when he turned seventy years of age. I loved the New Year festival atmosphere in the Country. We visited our relatives and friends in the host village of the year and enjoyed the delicious dishes and cakes in the big feast.

This local custom was discontinued in our district following the formation of the People’s Republic (1949). Sadly, my grandfather never received his ceremonial silver cup when he reached seventy in Hong Kong. However, after the death of my grandfather, a new festival running along similar lines of the old “District Feast” was organized in Hong Kong each year. The New Year Feast was open to all the people who came from the seven villages, both male and female, but everyone had to pay for the feast.

The women of these seven villages conducted in turn, an exhibition of their craft and folk art (女會) every year. The exhibits included dresses, embroidery, knitting, paper craft, dolls, painting and folk art. They would come to the host village of the year for the exhibition and at the same time visit their relatives and friends. My mother entered her needlework in the exhibition a few times, but I can’t remember whether she received any prize.

In the evening of the New Year’s Eve (除夕) and the evening of the Mid-Autumn Festival (中秋節), the children of the village would carry a lantern and parade in the street. Ma was always a big help to us in making various paper lanterns. But Nai-King would like to make his own lantern with a large Chinese turnip. He put a turnip in a bowl of water coloured with red dye for a few days then carved the turnip with a pocket- knife. He hollowed the turnip to put a small candle in it and made a few small holes to let the light shine through. When he lit the candle inside the turnip lantern at night, it gave a beautiful pink colour of the turnip and a twinkle of lights through the holes.

Flying kites in the open space was a favourite pastime for the kids in the autumn evenings before dark. We made our own kites with thin sticks and paper. We competed with each other to see who could fly higher and perform better manoeuvres with daredevil diving. We never had a kite dogfight, rather we tried to out do each other with kite making and flying skills.

Before moving into our new house in the village, my family shared a house with the family of our fifth uncle. It was a nicely built house about 100 years old. A secret small room was built in the house, behind my aunt’s bedroom. This hideaway was narrow about two metres wide without window or door. To enter this dark room we had to remove a large cupboard blocking the entry hole (a small window opening) located on the internal wall. My mother and aunt kept all their valuables in this secret room during the War.

We grew many kinds of vegetables and planted a few paw-paw trees on the land which grandfather bought for Ba’s new house. We also kept a few chickens for eggs and meat. It was a daily task of Nai-King and me to water the vegetables and collect the eggs. Winnie was small and couldn’t do much in the garden but helped Ma doing a few odd jobs in the house.

Ma received almost no money from my father in Hong Kong during the War. We lived mainly on the rent of the rice fields. Ma had to be very careful with the money, but we still had enough to eat. We had fish twice a week and meat (pork or beef) once a week, the rest of the meals were subsidized with egg, pickled vegetable and various home-grown fresh vegetables. We had the best rice for our daily diet together with chicken, duck and goose for special occasions. We dried our own tea from the young leaves of a local fruit tree every spring. We kept the whole year’s supply of tea in an earthen jug in a cool place in the house. Ma made pickled vegetables and Chinese sausages in autumn.

Toward the end of World War II, grandfather decided that it was time to build a house in the village for our father. (Attachment 3) It was a handsome two-storey house with a little courtyard between the front door and the kitchen. A well with nice clear water was dug in the stone-paved courtyard. All our houses were linked with an internal private lane. The children could visit each other without going out the front doors. There was no room in our new home for trees or lawn, therefore, Ma kept a few pot- plants in the courtyard to make it attractive and looking natural.

Our village was relatively safe from robbers and destruction of war. However, the Japanese soldiers came to our village twice, looking for the resistance fighters near the end of World War II. One of the Japanese soldiers went into my fourth uncle’s house and took a nice alarm clock from his bedroom. Luckily, the officer of the Japanese Army discovered what the soldier had done and made him return the clock to my uncle.

One day after school in 1944, our mother met us at the front door with a letter in her hands and told us the wonderful news, “Your father is coming home next month!” We were excited and didn’t know what to reply. It really was a long time since we last saw Ba (in 1941). I couldn’t remember what my father looked like, because I was only a two-year old boy when we escaped from Hong Kong. Ma didn’t know the exact date of his arrival, but she realised that he had to pass through the Japanese occupied areas and this could be dangerous.

One afternoon when I came home from school, I heard my mother talking excitedly to a strange man in the house, while my sister Winnie stood between the man and Ma. He had a short haircut and wide shoulders with a gentle voice. I hesitated to walk in the room where they were standing. Ma saw me and called me over to greet the stranger. In my memory, I never saw this man before and I didn’t know who he was. He came over and gently held one of my hands. I suddenly realised that the stranger was my father. I was excited and ran back to the front door to meet my elder brother who was walking with his friends behind me after school. He recognised Ba from the first sight and ran over to greet him. We were very happy and pleased that Ba had arrived home safely.

Sadly, my father came home just for a short visit and had to go back to Hong Kong looking after the family properties. He came home to see us, brief my grandfather on the situation in Hong Kong and discuss with my grandfather about the arrangement of building his new house in the village. Most of all he missed us so much that he couldn’t wait to see us. On the other hand, he longed for a good holiday without the bombing and unrest of Hong Kong.

We had a good time together during Dad’s stay in the village. He was very keen to know about our study. He made sure that we had done our homework before the evening meal each day. He talked to Mum a lot but did not mention any terrible War news to us. He was exhausted in caring for the family business in Japanese-occupied Hong Kong. Mum too longed for his gentle talks and assistance in looking after the demanding family.

Ba was firm but fair to all of us. One day he called all of us into his bedroom and measured our bare feet. Because he had found two footprints on the table and some of the lard in an earthen jar, which Mum left on a shelf above the table, was missing. He suspected that one of us took the lard without asking, but he had to prove it before he could decide any punishment for the guilty one. He measured our feet one by one and compared the footprints on the table. Ba found the guilty one and gave him the appropriate punishment.

It was sad to say goodbye to Ba when he went back to Hong Kong after his short visit with us. I was sorry for Ma because it was harder for her to see him off than us children. “I will bring you back to Hong Kong as soon as the War has ended,” Ba promised us, “We will be together again soon.”

On 6 August 1945, an American atom bomb dropped on Hiroshima with devastating results. Three days later another atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, resulting in the Japanese Government agreeing to peace negotiations with the Allies. That same month, Sir Cecil Harcourt steamed into Victoria Harbour at the head of the British fleet to re-establish the Hong Kong Colony. The citizens of Hong Kong were free to do their own thing again, after three years and eight months of Japanese occupation. Japan surrendered to the Allies on 14 August 1945 but didn’t signed the terms of surrender until 2 September the same year. The Japanese forces in China surrendered on 8 September 1945.

To celebrate the surrender of Japanese forces in China, the villagers built an arch at the entrance of the village, raised the national flag and let off plenty of firecrackers. The children had a day off from school to celebrate the victory over Japan, and most of all the end of this terrible War.

The village was full of life and hope again. A new era had started, plans were made to re-build and develop the country over the coming years. My parents also planned for our re-union in Hong Kong and a better life for their children.

We didn’t move back to Hong Kong immediately after the War, because the fourth uncle and my father had just set up a shop selling Chinese wines and cigarettes in Sham Shui Po, a suburb of Hong Kong. We agreed that we had to wait for a few more months before Ba could come back for us.

Early in 1946, Ma couldn’t wait any longer for Ba to come back to get us. She took Nai-King and Winnie, with the consent of my father, back to Hong Kong all by herself. I was left behind in the village for another six months.

It was not easy for Ma to make the decision of leaving me behind. She really couldn’t carry the luggage and look after three young kids in the long journey. However, I had the comfort that she would come back for me, as soon as they had settled down in Hong Kong. Further more, I would be well looked after by one of my older cousins while Ma was away in Hong Kong. My cousin would sleep in our house, cook the meals and wash my clothes. Before she went, Ma gave me a small sum of money for haircuts and pocket money. She told me, “You will be looked after by your cousin during my absence. You are a big boy now. You try to be brave, careful what you do and do it well. I will come back to get you soon!” She handed me an old family photograph, as a reminder of all of us.

My mother sent me a letter after they had safely arrived in Hong Kong. She told me they were well and father was always busy in the shop. My elder brother attended a public school and did well. My little sister was about five years old and longed to go to school. I knew that Ma was missing me too but didn’t openly say it in the letter. (The letter had to be read for me by my cousin). In order to cheer me up, she told me about their train trip from China to Hong Kong and the big ocean-going ships anchored in the harbour.

After they went to Hong Kong, my life in the village was not the same again. I waited and waited every day for Ma to come back to get me. I missed my family, especially missing Ma at night. When I wanted to play with my brother and sister after school, they were not there! However, my grandfather was good to me; he encouraged me to do well in school and gave me cake or biscuits from time to time.

About a half year had gone by without seeing my mother. I started to wonder when she could come back for me. However, my waiting for her return was not wasted. She returned for me toward the end of 1946, as she had promised. I was excited by the thought of going to Hong Kong and not sorry to leave the village where I had stayed about four years.

Early one morning, Ma and I left the village behind and walked with our simple luggage to the ferry terminal a few kilometres away. The ferry took us to Guangzhou for the early afternoon train to Hong Kong. I enjoyed the ferry trip by watching the boats in the river, the fellow passengers on board the ferry and the buildings on the riverbanks. But I enjoyed the train journey most because it was my first ride on a train since I could remember.

Ma and I arrived at the Kowloon Railway Station at Tsimshatsui, Hong Kong in the evening. My Ba with Nai-King and Winnie were already there to meet us. We were very glad to see each other again. Ma took one of my hands, walked to the waterfront a few metres from the railway station and showed me the big ships anchored in the harbour. I was so excited to see the ships, which I had dreamed of many times hoping that I could sail on one of these big ships one day.

One week after arrival in Hong Kong, Ma enrolled me in a primary school (佩文學校) opposite to our apartment. The school was small and run in an old fashioned way by a Mr Yee (余). Ma chose this school because it was near to our home and I could walk to the school by myself without worrying about traffic and distance. About one year later, my sister Winnie joined me to study in this school.

One day after school, Winnie was excited to tell me that we were going to have a little playmate soon. I was surprised by this news and couldn’t understand what she was talking about. Ma told me that she was expecting a baby - either a boy or girl would be added to our family. Winnie was so convinced that it would be a girl because it was fair for her to have a sister! I thought a girl was OK but a boy was even better for Nai-King and me!

Dennis (Nai-Por) was born in 1948, the year of the Rat. He was delivered in the birth clinic by the same midwife Ma had for me. He was tiny but had a strong cry. Our whole family were excited and looked forward to the celebration of this new birth.

It is Chinese custom to celebrate the arrival of a new baby one month after the birth (滿月) and we usually say that the baby is one year of age in the celebration! The family having the baby will invite their relatives and friends to celebrate with them.

A special helper was employed to help my mother to look after the newborn baby and the family, because Ma was not allowed to do any heavy housework and had to rest in bed most of the time, at least for the first month of the birth (坐月). Also, a specially cooked dish of ginger, pig’s trotters and boiled eggs in thick sweet rice vinegar was served to my mother every meal. Traditionally, it is believed that this will help the mother to recover quickly from childbirth and give her more strength, a good appetite and plenty of calcium for her milk.

For the celebration, my family pickled plenty of thin sliced young ginger in white vinegar (a good charm for many descendants) and dyed many hardboiled eggs in red (in their shells, for good luck and new life) to give to the guests. During the feast, my parents dressed the baby, Dennis, in red and showed him to the guests. The guests would give the baby a gift and congratulate my parents on the birth of their baby boy.

In 1949, the Liberation Army (解放軍) defeated the Kuomintang (國民黨) forces in mainland China and the Nationalist Government (國民政府) under President Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) fled to the island of Taiwan. Communist Chinese troops stopped at the border of Hong Kong and a Red Bamboo Curtain sealed off the Middle Kingdom (China or中國). The Colony could not have been defended had China ever decided to take it back; for the Chinese could have simply ripped down the fence on the border and sent the masses to settle on the Hong Kong territory.

While China’s civil war was being fought. Hong Kong’s refugee population swelled and the colony’s population increased to nearly two million. Many of the new refugees were affluent Shanghai entrepreneurs and proprietors, some arrived in the Colony with complete factories or large capital for investment. But most of the new refugees were poor and couldn’t speak the local dialect. The sudden influx of people from China provided a large pool of manpower for construction works and the growing light industries in Hong Kong.

In 1950, Chinese Communist troops joined North Korean Communists fighting the United Nations (UN) in Korea. In the following year (1951), Hong Kong’s lucrative China trade dried up as a UN embargo on the export of strategic goods to China took effect. Hong Kong was forced to change overnight from a mere transhipment depot for Chinese goods to a manufacturing centre.

The sudden increase of population in Hong Kong created a huge problem for the Colonial Government, especially for housing, jobs and education in the Colony. Many refugees squatted in small timber huts built on the hillsides near their work places. On Christmas Day 1953, a squatter area on the Kowloon Peninsula burst into flames leaving 53,000 homeless. This tragedy forced the Hong Kong Government to begin an emergency housing programme.

Fourth uncle and our father jointly owned a corner shop (合昌) in Sham Shui Po, Kowloon. The shop sold various Chinese rice wines and cigarettes. It was a small shop but the business was reasonable and earned enough money for the two families.

They bought the freshly stilled rice wine in large earthenware containers from the factory and added different ingredients to make various flavoured wines. The seasoned wine had to wait for maturity, between a few months to about one or two years, depending on the type of wine they would like to make. Some of their wines were sweet with beautiful perfume and nice in taste, but some of them were strong and unusual. The shop also sold very nice rice vinegar for cooking. My father did most of the blending of wines, which he had learned from the wine makers before the War. From time to time, my mother and our aunt had to wash the old glass bottles at the back of the shop and prepare them for wine bottling. Us kids would do the odd jobs in the shop and help to clean the shop windows each month.

My father spent most of his time every day working in the shop, except having his meals at home. He slept in the shop almost every night to ensure everything would be alright there. After school, we loved to go to his shop and had afternoon tea with him in a nearby café sometimes. Once a month in his day-off, Ba took Ma out to do something together. They might go to a film or Cantonese opera, or visiting somebody without us kids.

“Typhoon” is the Chinese word for “big wind (颱風)”. Typhoons can hit Hong Kong as early as May, but the peak season is from mid-July to mid-October. They vary in strength from tropical storms to severe super-typhoons. If one just brushes past Hong Kong, it will bring a little rain and wind that might only last for half a day (a level lower than 3 in the old typhoon warning scale of 10). If it scores a direct hit, the winds can be deadly and it may rain for days on end (a warning level above 3). However, in this age of weather satellites they no longer arrive without warning.

The severe typhoons can cause landslide, flooding, sinking boats, drowning and electric power blackout. When a typhoon becomes a possibility, warnings are broadcast continuously on TV and radio. During a bad typhoon (warning signal 3 or above), all of the schools and most of the offices and businesses are closed. Everyone goes home while there is still public transport. It would be prudent to stock up on food, water, candles, matches, a torch and batteries for a battery-operated radio if a big typhoon is heading for the Hong Kong territory.

I had experienced a severe typhoon (warning signal 7) in Hong Kong around 1950. The noise of the wind was very loud and terrifying. The wind was so strong that it needed the strength of two grown-up men to close the door of our veranda. Generally speaking, I didn’t mind the typhoon much because I would have a day (or days) off when a typhoon signal above three was issued by the Authority.

You can imagine what life would be like for all of us (grandparents and the families of their four sons) living in an apartment with an area approximately 30 feet by 80 feet. Our grandparents and the family of fifth uncle moved back to Hong Kong just before the communists took over China in 1949. Then were followed by the family of first uncle about two years later.

Life, indeed, was not easy for everyone in Grandpa’s apartment. But we had to make do in order to accommodate all the families. We had almost no privacy in the apartment and had to share the same kitchen and other facilities with others! Generally speaking, we were happy, well adjusted and learning to help each other. For us kids, we had a good time studying and playing together as a big family. It was so crowded in the house and we were almost on top of each other. Therefore, some conflicts between the families could not be avoided, either due to the children or personalities. Fortunately, it didn’t happen very often and wouldn’t last long. Usually, all differences amongst the family members would be resolved before the family celebrations, such as birthdays and the major festivals of the year.

When our grandfather was getting older and finding it harder to walk to his favourite restaurants, he would ask us kids to buy the dim sum, cakes or sandwiches for him. He always bought more than he wanted in order to share with us. One evening he wanted to have his supper with rice, but no adults were home to cook for him. Winnie, my ten years old sister, had volunteered to cook the supper for him. She had never cooked any rice all by herself before, but was willing to try. She served the supper to grandfather before our mother had arrived home. Ma was surprised what Winnie had managed in the kitchen. However, she thought that the rice was not quite cooked and might be hard for grandfather to eat. However, our grandfather assured mother that the rice was perfectly cooked and he liked it!

VI. THE CHANGING POINT OF MY LIFE

My family held a traditional Chinese belief, a mixture of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism and ancestor worship. We never heard or knew anything about Christianity until we attended a church school at the next suburb. Most of the Chinese may refuse to accept Christianity because it comes from the west, is not Asia, and it objects to the traditional ancestor worship. I saw once or twice the missionaries evangelising in our marketplace, but I never listened to their message long enough to understand it!

You may ask why I changed from my old style school to a modern church school. The only answer I can give is that it was God’s plan. During the 1951 summer school holiday, my aunt was concerned about the academic performance of our old school, especially in science and English. She enrolled her children in a church primary school at the next suburb for the coming school year and advised my parents to do the same.

My new school, Semple Memorial School (深培學校), was an out reach of the South China Foursquare Gospel Church, Hong Kong (香港華南基督教四方會). It was located in a quiet suburban street, opposite a large open-space with soccer ground and running tracks. The ground floor of the school building was used for kindergarten during weekdays and church during Sundays. The other three floors of the building were used for primary school classrooms and offices.

Every morning we spent the first half hour for devotion in the classroom, through the school public address system. We sang hymns and choruses, then studied the Bible before starting our normal school lessons. Also, we were required to attend Sunday school each Sunday morning. All these singing and praying things were new to me. I was not used to it from the beginning and even rejected it secretly. However, God’s way was not my way; without me knowing it, the good news of God had already taken root in my heart and my response to His calling was just a matter of time. (Photo 7)

I studied hard for my fifth year of primary and did very well in the new school. By the end of the school year I was used to the church school life and even loved the caring and friendly atmosphere in the class. I commenced my final year of primary education in September 1952 and fell sick one month after. This sickness changed my whole life and direction.

In the beginning, I felt short-of-breath when I walked up stairs. My family doctor couldn’t find out the cause of my sickness and treated me for an ordinary virus or cold. After a few days, it became hard to breathe when I slept flat on my back. In order to get some sleep at night I had to sleep in a half sitting-up position. It was a big worry to my parents and family.

One of my cousins (若芝) was a trained nurse and worked in a big hospital on the Kowloon Peninsula. She suggested to my mother to take me to a specialist, a friend of hers, practising near her hospital. In the first visit to the doctor, he diagnosed that I had an enlarged heart (rheumatic fever), which could be treated with a new drug. He also instructed me to stop my studies immediately and rest at home until I felt much better. He was confident that I would live a normal life when I’d grown up, because I was young and the sickness had been treated early.

I was disappointed that I couldn’t go to school and my sickness might delay my primary schooling for one year. My family too was very worried about my sickness and concerned about the medical expenses.

In these circumstances, the only thing I could do was obeying the doctor’s instructions by receiving his treatment and resting at home. My cousin was good to me; she gave me the necessary injections and provided plenty of Vitamin B tablets for my recovery. I didn’t know why I had to go through this trouble and suffering. But I prayed that I would recover soon and could go back to school without delaying my schooling by one year.

Thank God that I responded to the new drug very well. I could breathe more easily just after a few treatments. However, I was lonely at home while the other kids went to school during daytime. I couldn’t sleep very well at night (as I slept too much during daytime) and started to think about my future. The doctor told me that I should not play any sport nor take up any high demanding stressful job in the future, even after I had recovered from this illness.

I was depressed by this limitation and wondered what I should do when I grew up. My heart was heavy and burdened. I started to pray and asked God to cure my sickness and give back my strength. I diligently read my Bible every day and eagerly sought God’s wisdom and advice. One day God opened my eyes to see that I should not worry about my future because He would protect and guide me. I started to care for others and pray for the people around me. To follow Christ I had to repent of all my wrong doings and obey His commands. I was comforted by His promise: “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest.” (Matthew 11:28)

After I had made the commitment, the speed of my recovery was amazing and I was allowed to go back to school in early 1953. During my long rest at home, one thing touching me very much was a visit by my classmates; all the boys and girls of my class. They even brought some fruit for me and wished me a quick recovery.

After going back to school, I studied very hard to catch up the missing four months schooling. It was difficult in the beginning, but I was willing and knew that God would give me the necessary strength and wisdom.

With my new faith and strength, I eventually sat for the final examinations of the primary. I passed all the subjects with good marks! I had never dreamed that I could achieve such a good result, but I was always confident I would pass allowing me to study in a high school.

Following the excitement of my primary school graduation on 5 July 1953, I put my head down again to prepare for the high school entry examination. I enrolled in two Christian high schools and sat for the entry examinations. I was accepted into All Saints High School (諸聖中學). My cousin Tony was also accepted into this school.

In September 1953, I commenced my high school years in All Saints High School. It was an Anglican Church school and located with the All Saints Anglican Church, on the Kowloon Peninsula.

This school offered all classes from the first year of primary (Year 1) to the final year of high school (Leaving Certificate). The classes were conducted in two groups: the morning group (from 8:00am to 12:30pm) and the afternoon group (from 1:00pm to 5:30pm). I attended the afternoon group in the school while my cousin Tony attended the morning group. There were about 45 to 50 students in each class. Sometimes it was hard to work in the laboratory because of the large class size. The Principal was one of the Bishops in Hong Kong. I took about 45 minutes walking one-way to attend my school each day. I could catch a bus to school and save time and energy, but I couldn’t afford the fare everyday!

All students were required to attend school assembly in the Church each Wednesday, before we started our lessons. We sang hymns and read from the Prayer Book. One of the teachers gave a 15-minute talk (not limited to biblical topics) and another teacher announced the school news of the week. We would also have special worship services for Easter and Christmas.

After I started All Saints High School, I developed a reading habit because of the ease of access to the libraries near my school. I visited the American Cultural Centre almost once a week. I also obtained library cards from the Elizabeth Library and Mengs (孟氏) Library. Visiting the library was a cheap and enjoyable way to spend my summer holidays in Hong Kong, not to mention enjoying the air conditioning in the American Cultural Centre.

I studied very hard and was pleased with what I had achieved in the first high school year. In July 1954, a certificate of excellence was awarded to me by the Principal to recognize my hard work.

In September 1954, my cousin Tony and I planned to transfer from our Chinese high school to a Catholic English college on Hong Kong Island. Tony got into that college but I did not, because I was one month older than their age limit. I felt sad over this event but I knew there must be a good reason that God didn’t want me to study there.

I continued my second year study in All Saints High School and worked even harder in order to achieve a better result than the previous year. After I finished my mid-school-year examinations, my uncle who taught in Clementi Middle School (金文泰中學) informed me, “I can get you into my public school if you don’t mind travelling to Hong Kong Island every day.” Thank God, of course I didn’t mind travelling across the harbour. I told my uncle that I would love to study in his school - the only Chinese high school run by the Hong Kong Government.

Now you can see how God planned and guided my every step. Even though I had gone through sickness and disappointment, His way was still the better way! The Clementi Middle School was set up by the British Colonial Government to commemorate a former Hong Kong Governor, Clementi, who could read and speak Chinese fluently. The teachers and facilities of the school were very good and the school fees were much cheaper than the previous school. It was a big help to my father, financially.

The classes in this school were conducted in two sessions: The senior high school classes were held in the morning session, from 8:00am to 12:30pm, and the junior high school classes were held in the afternoon session, from 1:00pm to 5:30pm. I attended the second year of the junior high school afternoon session in early 1955 (the second half of the Hong Kong school year). I didn’t feel lonely as a new student because my elder brother and cousins were already studying in this school. However, I had to share the desk with a girl because it was the only empty seat available for me in the classroom!

The School was situated about half way up the hill, near the Peak Tram Terminal, on Hong Kong Island. The Japanese Army commandeered this building for their offices during the Hong Kong occupation. It was a beautiful colonial style three-storey building, with tall palm trees in the garden and an outdoor basketball court in between. I could see part of the Victoria Harbour through the first floor windows. In front of our School, was a church-run English college for boys, and behind us was another private high school for both boys and girls. It is funny that I never made any friends with the students who attended these other two schools!

I enjoyed the ferry trip across the harbour each day. The view of the harbour was magnificent no matter whether day or night, and the breeze on the ferry was comforting in hot days. It took me a half hour walking from the ferry terminal to the School. I could catch a bus but it would cost me and didn’t save any travelling time due to the long bus route. I would rather walk through the garden of St John Church and listen to the singing of the birds than by using a shortcut to school. Sometimes, I even went in the church hall to see the painting or photograph exhibitions before or after school.

We had two main activities in the school calendar: Christmas celebration and athletic week. A social evening would be organised to celebrate Christmas after our mid-school-year examinations. Students and teachers were invited to take part in singing, dancing, poetry reading, drama and performing magic in the Christmas function. Other students and teachers would be involved in many tasks to assist the performance. One year, the teachers decided to perform a drama in the Christmas celebration. My uncle was one of the teachers who took part in that play and he did very well indeed in that social evening!

In late spring each year a week was set aside by the School for the annual athletic competition. I, alone, was not allowed to attend any of the sports because of my previous heart problem. But my brother and cousins would take part in a number of competitions, such as running, jumping, etc. My brother even won one or two prizes in the school athletic competitions.

For individual classes in the school, we might organise our own social activities, such as a dance in someone’s home or a picnic in the countryside, from time to time. I learned to enjoy classical music when I was in senior high school, due to the influence of a young and keen music teacher. I also learned and became appreciative of arts in my high school years. Our art teacher was a successful artist, especially in watercolour painting. He taught us many types of drawings, including coloured pencil drawing, watercolour painting, sketching and Chinese painting. The School had a nice study environment and the excellent teachers and facilities compared favourably with the top schools in Hong Kong.

In 1956, another wave of refugees hit the Colony and pushed the Hong Kong population above 2.5 million. Squatter huts sprung up everywhere and rioting between Nationalists and Communists exploded in the Kowloon streets.

The situation was very serious and dangerous because of the involvement of gangsters. Shops were robbed and many innocent people were attacked by mobs. The Government called in the reserve police and defence forces to install law and order in the Colony. The riots continued on the Kowloon Peninsula for three days and eventually were brought under control again.

I saw the fighting, burning and destruction of cars, traffic lights and properties in the streets. I had experienced tear gas and shooting in our suburb. Many people were arrested or disappeared and never found again! It was a terrifying experience, which one could not easily forget. The second time I faced another street riot in Hong Kong was in 1967, the year I returned to Hong Kong after I had finished my study in Australia and was on my way to Canada.

Chinese New Year marks the start of the lunar calendar and is celebrated around the end of January and the beginning of February. In the old days, it went on for a week but nowadays it is a three-day holiday. During the Chinese New Year holiday (or Spring Festival 春節), just about everything closes down except the essentials.

The festival is a family one, houses are cleaned, debts paid off and any differences must be made up before the New Year’s Day. Pictures of gods are pasted up around the front doors of houses to scare off the bad spirits, also with messages of welcome on red paper to encourage the good ones. All children are looking forward to collecting “lai see” (利事 or lucky money) in small red envelopes from their elders. The people greet each other, “Kung hey fat choi (恭喜發財)” –literally ‘good wishes, good fortune.’

When I was a kid, I couldn’t wait for the Chinese New Year after the Christmas holiday. At the Chinese New Year’s Eve, I would visit the huge and exciting New Year Market (年宵), which was set up especially to sell all sorts of goods and flowers for the Spring Festival. It would run for a few days before Chinese New Year’s Day. The people bought lucky peach blossoms, kumquat trees and narcissi from the hundreds of flower sellers. (The peach is regarded as a symbol of longevity; the Taoist God of Longevity, Sau Shing-Kung 壽星公, with his white long beard and enormous dome-shaped head, is believed to have emerged from a peach). In the Chinese New Year’s Eve I would go to the fair (or market) with my cousins after tea and stay there until almost mid-night! The place was jam-packed with crowds. I would sample the delicious snacks from different stalls and hunt for bargain flowers for my mother.

Chinese opera is an integral part of Chinese cultural entertainment and originates from China’s earliest folk music and dances. During the 18th Century, Chinese opera came to be associated with festivals and state occasions at the Imperial Court in Beijing. However, Chinese opera is a world away from La Boheme in the west. It is a mixture of singing, speaking, mime, acrobatics and dancing that often goes on for five or six hours. Cantonese opera is one of the three types of Chinese opera (Cantonese, Beijing and Chiu Chow) performed in Hong Kong. The Cantonese variety is more ‘music hall’, usually with a ‘boy meets girl’ theme and often incorporating modern and foreign references. It is considered less traditional but has the largest following in Hong Kong.

A traditional Chinese orchestra accompanies the singing artists of the opera, who usually speak and sing in a specific local dialect. Musicians playing percussion instruments occupy one side of the stage while others responsible for wind and string instruments sit on the opposite side, leaving the main area of the stage clear for the performers. Makeup, movements, props and specific costume colours identify an actor’s age, sex and personality the moment he or she appears on stage. My parents were keen Cantonese opera followers.

When I was a kid, I went to the Cantonese opera performance with my family a few times each year. I liked the moving story of the opera and the acrobatics, but I disliked the long-hours and coming home late, always after mid-night!

When I was in my teens, I was too busy with my study and couldn’t afford to spend five or six hours watching an opera performance. Sometimes, I might listen to the live broadcast of opera performance from the local radio stations, but it was so noisy and distracting from my work, especially at night.

If you walk down the side streets of Hong Kong, especially at night, sooner or later you are bound to hear the unmistakable sounds of a mahjong (麻將) game in progress. Mahjong to the Chinese is not just a game. It is a habit-forming social event, a virtual way of life, which can be as addictive as cigarettes, alcohol or drugs.

Mahjong is played with coloured tiles made from bamboo or plastic and engraved with patterns and Chinese characters. The game is often played far into the night and drives other people mad because of the noise accompanying it. How can I describe the sounds of a mahjong game? It is something like this – the clickity-clacking of the tiles rubbing against each other during the shuffle, sharp banging noises as tiles are slammed on the table top with each call, and loud shouts announcing each call.

Mahjong is a popular game at social functions in China – it is even heard clacking at dinner parties, banquets and wedding celebrations. It is played almost everywhere, by anyone and at any time -- at the beach, building sites and in factory canteens. Some mahjong fans insist there’s as much skill involved in betting during a mahjong game as there is in backgammon or bridge. The game is so popular in Hong Kong that there are licensed mahjong centres where one can meet other players and gamble all-day or night!

The game of mahjong appears to be anything but a game of leisure and relaxation, Chinese-style. It also is used as a conclusive Chinese test of an unknown man or woman’s mettle. Indeed, an old Chinese saying advises that if one wishes to find out what kind of man his daughter is going to marry, the best way to find out is to invite him over for a “friendly” game of mahjong.

I do not play mahjong even though I learned to play it when I was a boy. I can’t sit still and play for hours far into the night. I would rather play bridge or a board game with my friends, as which is not accompanied by loud noise and doesn’t take up hours of my time. The main reason for my rejection of mahjong was because of a big argument between my parents caused by mahjong playing and they didn’t talk to each other for many days.

I loved hiking and camping in the New Territories (新界) during summer holidays. The clean air, light breeze, gentle surf, fine sandy beaches, green hills, singing birds, colourful butterflies, various vegetations and beautiful but tranquil scenery of the countryside refreshed my body as well as my soul and helped me to get going again in the hot and humid Hong Kong summers.

One day during my summer holiday, my cousin David (乃般), a friend of ours and I went for an afternoon hike to the “Three Folded Pool (三疊潭)” in a small valley at the foothills of the Lion Rock (獅子山), near the Kowloon side railway tunnel entrance. It was a hot and breezeless day, but we hoped that we could have a little play in the water when we arrived there. Unfortunately, there were five wild boys waiting for us at the pool, who robbed us. They took my pocket-knife, our friend’s cinema ticket and a small amount of pocket money from my cousin David. We couldn’t fight with them even if we wanted to, because we were out numbered!

My cousin Tony was a Boy Scout who knew all the camping stuff in the family. One weekend in our summer vacation, Tony, his brother David, a friend of ours and I caught a bus to Sai Kung (西貢) district in the New Territories for a camping “expedition”. The weather was perfect and we were eager for a long hike from the bus terminal, each of us with a heavy pack on our back. We talked to each other and enjoyed ourselves when we walked on the narrow country path. We found an ideal campsite beside a small creek with trickling water. It was half hidden behind some bushes from the walking track. The tent was set up for the night and a campfire was lit to cook our tea (dinner). After having our meal, we cooked some rolls, with bread dough twisted around a stick over the fire for our supper. It was heaven that we were able to sit around the campfire, eat the freshly “baked” bread rolls, discussing almost everything and watching the stars and the half moon in the clear sky, late into the night. It was nice and peaceful in the camp until Tony cut his hand on an opened tin can, when we had our breakfast the next morning. We applied first aid on his hand immediately and put it in a sling. He was shocked by the accident and worried that his hand might be infected. After consultation, we decided to pack up the camp and went home with Tony.